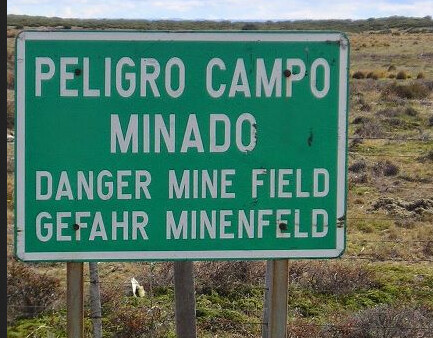

Perhaps its just coincidence that the Carretera Austral extension was executed by the Chilean Army engineers, during a time of heightened tensions with Argentina, but I would argue that the colonization of this inhospitable region owes more to geopolitical concerns that to any real attempt to develop it.

Looking further back, I recall reading that formal colonization was only promoted by Chile in the 1920s, in an attempt to curb Argentinian influence in the area. Before then, Chilean state presence was barely perceptible, as opposed to stronger Argentinean influences, at a time when that country was wealthy while Chile languished in its post-WW1 poverty.

One of the missions of the region’s first Intendente was to reinforce the “Chileanization” of the region, to counter Argentina:

(Original here)

"..After almost 30 years of land concessions, when the newly appointed Intendente, Luis Marchant, a colonel of the Carabineros, arrived in the winter of 1928, he was confronted in Puerto Aysén by a “miserable, rustic pier in a deplorable state…By mandate of President Ibáñez, Marchant’s mission was to create the foundations of a system of domination that would strengthen Chilean identity in Aysén.”

"..The process is carefully chronicled by the diplomat and writer Víctor Domingo Silva, then Chilean consul in Bariloche and Chubut, who points out in The Tempest Is Coming (1936) the differences and imbalances between the Chileanization and Argentinization processes of Patagonia, arguing that this material and symbolic impetus of the Argentines would make the national population of the border areas very vulnerable. Giving strength to the argument that border populations do not respond to national identities, or that they are neither Argentine nor Chilean, and that they routinely circulate from one side of the low mountain range to the other through a commercial, labor, and family network of political and blood ties…there is a "culpable neglect by our administration, which has been, gradually but persistently fueling and strengthening the Argentinization of these regions"

Regarding the “Colonization” efforts, even early on, these had led to widespread devastation, and the following quote also includes several acid comments on the Region’s suitability for human development.

“…At the same time, an ecocide took place. In 1933, Latcham noted that the forests were almost impenetrable, a result of swamps and reedbeds, so “clearing” was used to introduce more livestock, destroying “enormous tracts of forest”, in what would become — between 1920 and 1940 — “a legalized burnoff”. Everything was precarious: a lack of good ports, roads, animal transport, and poor communications. Cold, rain (2 to 4 m3 annually), food shortages (legumes, fruits, and vegetables), dependence on Argentinean stores for everyday needs, and a permanent lack of medicine and clothing prevailed. The average temperature of 12°C recorded in January in southern Aysén explained and sanctioned "the region’s weak aptitude” for agriculture.

This is what Google had to say: