In the 1970s, long before I settled in Magallanes, I was in the Norte Grande. The Atacama. And I haven’t exactly stayed away, since a few years ago I was working with an Argentine historian on the Butch Cassidy/Wild Bunch connections to that region. Antofagasta, to be specific. Since yes, they got in trouble there was well. Shot a man in Anto, just to watch him die. But that is another story for another time.

Those early days were enlightening. I found reason to give the Carabineros a glowing newspaper report during the first time I was interviewed by a regional paper here. Also another story, for another time. And just south of Arica I found part of a human skeleton along the road, en el medio de la nada. Think nothing of it, I was told at the time. Had I not been inured to such things as a former soldier, it might have bothered me.

Just outside of Antofagasta we noticed a sandy track leading off to the ruins of an abandoned nitrate mining operation, the likes of which were known as oficinas salitreras. This was the 1970s and a lot of those sites had not yet been vandalized. Not even a spot of graffiti. The locomotive and rail cars looked as though they might be restored to operation.

Through an opening in a window we could see things the way they were left – a typewriter, furniture, and some ancient electrical devices that belonged in a museum, all covered in that pervasive Atacama dust. No, we did not violate that building.

One did not need to be any sort of historian to know that at the beginning of the 20th century, the working conditions in those nitrate operations were hideous, inhuman, and most of all, unhealthy. And while much of the Earth sported their own epidemics at the time, it was “the plague” – or plagues-- that affected, and decimated, the cities and mining operations of the region.

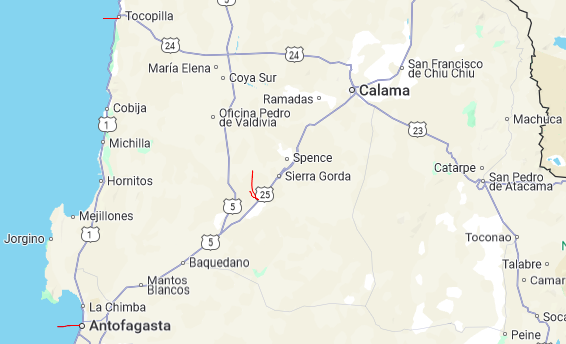

Although epidemics that included yellow fever were recorded in the mining towns as early as 1903, the worst of it, it seems, started in 1912 with the arrival of a ship from Ecuador that docked in Tocopilla. One of the crew members carried bubonic plague. It spread to the dock workers and soon enough devastated the north of the country. The histories of the region recall that it hit the children under ten the worst. The bodies of the dead still carried the illness and had to be buried at some distance from the surviving populations.

As you drive west from Calama on the highway toward Antofagasta, the remains of the nitrate operations are readily visible. About 5 km before reaching the pueblo fantasma of Pampa Unión, to the north of the roadway you may spy the cemetery that came to be known as either (or both) the Cementerio de los Apestados, or El Cementerio de los Niños.

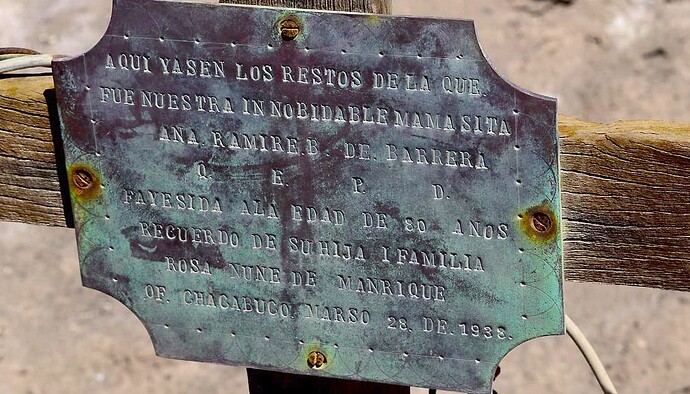

Evidently, this cemetery was used through the 1940s, after the plagues and other epidemics had passed, and for burying the elderly, as evidenced by the dates and ages on the graves. But most of those buried here were scores of anonymous children, and their simple Latin cross markers bear no names or other identifying information.

Walking slowly around this cemetery and observing the ages of the young dead, I was reminded of my own aunt, who also died very young, and whose tomb was chipped and carved into the frozen tundra in Canada’s Northwest Territories.

There is no shortage of places in Chile to experience immense sadness. Here, under the punishing sun and the lifeless, barren ground, is certainly one of them.

8 November, 1929, at the age of 3 years